October 10, 2013 by admin ·

Questlove reflects on life, his career, and the art of music.

By Aazim Jafarey

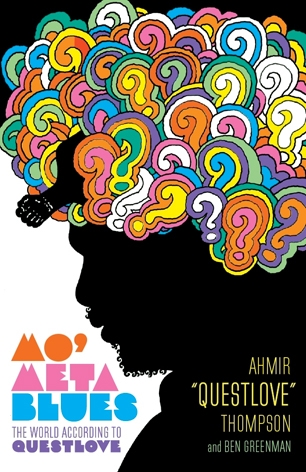

Credit: Grand Central Publishing via Rolling Stone

Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson wears many hats (metaphorically, of course; his impressive afro nullifies any need for head decoration): co-founder and prolific drummer of legendary hip-hop band (and Late Night With Jimmy Fallon cornerstone), The Roots, highly-esteemed producer, DJ, music journalist, and more. As a result, his musical knowledge is perhaps unparalleled in both its scope and depth. And yet, on the cover of his brilliant new memoir Mo’ Meta Blues, he is depicted as merely a shadow: his face, beard, and a comb jutting from his afro are all outlined in black against a white background. This rather bland design is juxtaposed against Questlove’s afro, which is adorned with psychedelic question marks, outlined in piercing shades of blue, green, orange, and yellow.

As confusing as this cover idea may seem, the art fits the book perfectly. Unlike most hip-hop memoirs, Questlove’s book is not merely an autobiography. Sure, Mo’ Meta Blues is filled with plenty of anecdotes: of his youth, of The Roots’ formative years, of collaborating with and meeting other acclaimed musicians, such as J Dilla and D’Angelo. If the memoir was composed solely of these tales it would still be a compelling read; after all, who doesn’t want to read about late-night figure skating with Prince and Eddie Murphy or Tracy Morgan’s unmatched craziness? Yet what truly makes Mo’ Meta Blues a must-read is its author’s reflectiveness. Much of the book takes place in Questlove’s thoughts, and it is clear that his eclectic mind is a busy place. He frequently espouses novel theories; at one point, for instance, he refers to the 1995 Source Awards as “hip-hop’s funeral.”

His contemplative nature is not only fixated on external affairs; as the title suggests, Questlove takes a ‘meta’ approach to his writing. He meditates on what it means to write a memoir – what stories he should tell, how much of a particular anecdote he should reveal, etc. Not only does he acknowledge that Mo’ Meta Blues is an unconventional book, he actively highlights it. Indeed, the uniqueness of Questlove’s approach is even evident in the way the book is formatted; the first few chapters are structured as a rich Q&A session between the acclaimed drummer and longtime Roots manager and producer Rich Nichols, who later adds commentary via footnotes. At times, the two disagree over the facts of a story, or reach differing conclusions as to its meaning. These inconsistencies, which would likely be avoided in most other memoirs, are fully embraced. In other chapters, email exchanges between co-author Ben Greenman and his editor are reprinted with no further commentary, providing an outside look at Questlove, his busy schedule, and the making of the book itself.

Questlove’s passion for music is remarkable – at one point he reveals that whenever The Roots finish an album he writes a mock Rolling Stone review predicting the score and comments that the work will receive – and Mo’ Meta Blues shines because of it. Music is, quite simply, Questlove’s life and he makes sure to give it a voice in Mo’ Meta Blues. He frequently makes allusions to songs, artists, and albums, and even has a recurring segment called “Quest Loves Records” in which he touches on the most important records of each year of his youth.

Quest states plainly at the very beginning that he does not want his memoir to be an “average book,” and with the help of his unique musical perspective and entertaining anecdotes he fully succeeds.

Aazim Jafarey is a junior at Columbia University majoring in Urban Studies. Originally hailing from the Greater Boston area where he graduated from Phillips Academy, Aazim is an avid music listener and hip-hop enthusiast. In his spare time, he is a freelance rapper who records under the pseudonym, Lucid Dreams. You can check out his music at soundcloud.com/iseelucidly and can contact him at [email protected].

October 10, 2013 by admin ·

iTunes Radio stirs up the streaming world.

By Justin Harmond

Pandora, Spotify, Rdio, Slacker, etc. Just when it seemed like the music streaming ecosystem couldn’t get any more saturated, Apple announced its new plans to release iTunes Radio – a new music streaming service, available to iOS 7 users, that will come standard with every new Mac device released this fall. Though the program will only be available in the US to begin with, there are plans to roll it out in other countries beginning in 2014.

Functionally, iTunes Radio most closely resembles Pandora. Users can build personalized radio stations based on different songs or artists. As you listen to the radio station more, users are given the opportunity to customize their listening preferences further, telling iTunes to “Play More Like This” or to “Never Play This Again.” Just like Pandora, iTunes Radio gives users the option to add variety to their stations by including other artists or songs as well. On iTunes Radio, a user can also configure a station to play more top hits, more indie gems, or an equal mix of both. Both Pandora and iTunes Radio are ad-supported and thus free for users. In my experience playing around with iTunes Radio, ads run sporadically and consist of short 15-second clips from the Ad Council, among others. If you don’t mind shelling out $25 each year to use Apple’s iTunes Match service, you’ll be able to use an ad-free version of iTunes Radio. While Pandora and iTunes Radio may sound too similar to make you want to switch services, Apple’s position as one of our generation’s biggest and most beloved technology companies distinguishes iTunes Radio from some cheap Pandora clone. Allow me to elaborate…

As the company behind iTunes, the largest digital music store in the world, Apple already has access to an incredibly large range of music. Everything that is featured on the iTunes Store will be available on iTunes Radio. This also means that iTunes Radio users will gain access to iTunes exclusives before they come out anywhere else. Anytime you see an up-and-coming band release the free song of the week or your favorite artist releases a track for buying a pre-order of their next CD, you’ll have immediate access to it on your radio station. Having access to all of this music allows iTunes Radio to make well-informed predictions on what music you might like based on what songs you already have in your iTunes library and the purchase history of other iTunes users. I find that the stations I build on iTunes Radio are more spot-on to my listening preferences than the ones I build on Pandora. After making a few adjustments to my radio station, I rarely find myself having to skip a song. If you rather not build your own station, iTunes Radio gives you access to curated “Featured” stations and 200+ genre focused stations. If post-punk revival music is your jam, iTunes has you covered. Apple does a great job of chronicling your play history as well, providing a full list of the songs you’ve listened to. This makes it very easy to backtrack and find that song that instantly sent shivers down your spine. If you’re one who likes to buy your music, Apple makes it effortless to impulsively buy the song you’re currently listening to. All you have to do is press the conveniently placed “Buy Song” button next to the song information. Ideally, this will ultimately lead to an increase in legal music downloads.

On that note, if you’re one who follows the ever-evolving debate over streaming royalties for musicians, you’ll be happy to know that iTunes Radio pays more to the label for songs than Pandora. They even give labels a percentage of their advertising revenue. On top of all of that, the royalty rates being used by Apple to play artists will increase over time. As streaming services become more commonplace and the number of users on iTunes Radio increases, artists can expect to make more money off of streaming in the future.

Only time will tell if iTunes Radio will truly take off. That being said, there’s no real reason why it shouldn’t. With iTunes Radio, anyone who has iTunes or an iOS device in the United States has access to a vast musical library without ever having to own any music or install any outside app. iTunes’s all-encompassing music catalog means it is highly likely you’ll come across the music that you enjoy. And their knowledge of users listening preferences makes it easier to discover your new favorite artist! As the music industry tries to create new sources of revenue for artists, Apple is leveraging their influential position as a technological and musical powerhouse to bring streaming to the mainstream…no pun intended.

Born and raised in New York City, Justin Harmond is currently a junior at Columbia University studying Anthropology with a focus in Music and Business. He first realized his interest in the music industry in high school after founding Phillips Exeter Academy’s first hip-hop club, ERA. Since then, he continues to stay involved with the music scene, sitting on the board of the Columbia University Society of Hip-Hop (CUSH) in addition to having previously interned at Babygrande Records and iHipHop Distribution. This summer, Justin took a break from working in music to explore his interests in advertising while interning for ad agency Goodby, Silverstein & Partners. When he’s not living and breathing music, Justin spends his free time playing basketball, video games, and scouring tech blogs for the next big thing.

October 10, 2013 by admin ·

By Aazim Jafarey

Now that we are approaching the mid-2010s and the “Age of Social Networking” is truly upon us, there is a new barometer for determining the importance of a pop culture event: social networking traffic. If something is small yet still worthy of note it pops up in your timeline – a new Juicy J song, perhaps. If the event is of more widespread significance, it registers as a trending topic, a la #BreakingBad or “THIS SH*T IS FIXED AINT NO WAY” (after the devastating Spurs loss in Game 6). In the case of the power outage at last year’s Super Bowl, multiple trending topics might appear, and in the rare instance of something as pervasive as Michael Jackson’s death, Twitter may even crash altogether.

Using this scale, Kendrick Lamar’s verse on Big Sean’s “Control” fell short of the top tier – but not by much. The day after “Control” was released, Twitter was flooded with comments. At one point every trending topic was related to Kendrick. His peers tweeted their acknowledgments, and pioneers like Big Daddy Kane tipped their hats and reminisced about the early days of hip-hop. Some fans posted pictures from the already-iconic “Source” photo-shoot in which “King Kendrick” dons a crown; others passed along memes mocking the rappers that K-Dot name-dropped (particularly Drake and J. Cole). The verse was so pervasive that it was even featured on an array of non-hip-hop websites, and by mid-afternoon everyone from Business Insider to TMZ had written about the Compton rapper’s verbal assault. (Of course, TMZ subtitled their article with “Lindsay Lohan’s a Pathetic, Porsche-Smasher”, so perhaps their inclusion should be taken with a grain of salt.)

Within 24 hours it was clear that Kendrick’s “Control” verse would be looked upon as one of, if not the, most notable event of hip-hop in 2013. The inescapabilty of the track was a direct result of two major factors: the content of Kendrick’s lyrics and the context within which the song was dropped. Taken by itself, the verse is certainly remarkable. Since the album “good kid m.A.A.d. city” was released in 2012, Kendrick has been a frequent contributor on other artists’ songs; the only other rapper with a comparable résumé is 2 Chainz. For this reason, the impeccable delivery and flow that he uses on “Control” are, although impressive, not particularly notable – for K-Dot, such technical skills have come to be expected. What sets this particular guest appearance apart are the actual lyrics that Kendrick viciously spits. For one thing, the verse is filled with nods to other hip-hop legends: the line “I don’t smoke crack, motherf***a, I sell it” is an inversion of an Eminem line, he references and then immediately shouts out West Coast legend Kurupt (the verse as a whole is at times reminiscent of Kurupt’s “Callin’ Out Names”), and, of course, the “Kendrick, Jigga, and Nas” line is an allusion to a lyric that Hov once spat and Nas later flipped on “Ether.” At times, the verse is straight-up poetic: “Live from the basement, church pews and funeral faces”; in other instances, it is bluntly egotistical: “I’m Makaveli’s offspring, I’m the King of New York/King of the coast, one hand, I juggle ‘em both.” (A random aside: while likely unintentional, Kendrick’s “King of New York” line reminds me of a Kanye bar from a 2008 song by then-G.O.O.D. music signee Really Doe, when ‘Ye spit, “I’m the king of the world, so the king of your city by default.”)

The true crux of the lyrics lies in his name-dropping; he is able to tip his hat to his peers (“I’m normally homeboys with the same n**** I’m rhyming with”) and then immediately declare, “I got love for you all but I’m tryna murder you n****s/Tryna make sure your core fans never heard of you n****s/They don’t wanna hear not one more noun or verb from you n****s…” He lists eleven MCs in a row, simultaneously labeling them as notable artists while also proclaiming his superior ability. Taken in totality, it is clear that this verse is not meant as a diss to these other rappers; at no point does he echo Tupac by proclaiming “f**k your b***h and the clique you claim.” Instead, Kendrick is attacking hip-hop as a whole; if no one else is willing to spark competition, then he will be the one to do so.

In this regard, the context of the song – modern-day hip-hop – is very telling. It’s 2013 and rap is a far cry from what it used to be. There is no denying that in the 1990s rap was much more competitive. The frequent collaborations that one sees today are a phenomenon that has steadily increased since the mid-2000s. Some of this change was necessary; after losing both Tupac and The Notorious B.I.G. (as well as countless of other talented MCs whose names are far-too-frequently forgotten) to gun violence, it was clear that the raw nature of hip-hop needed to be subdued. As hip-hop was growing accustomed to a bigger spotlight, artists who had been raised in violent environments were bringing the streets into the music industry, and creating a dangerous environment for their fellow musicians. However, following the deaths of Biggie and Tupac, it was necessary to quell the physical violence that had arisen, and as such there is no denying the decline in competition that resulted. The raw lyrics that appeared frequently in the ‘90s now seem restricted to underground artists, with only a lucky few able to attain commercial success without adopting a pop-friendly style.

Moreover, the originality has declined. In the ‘90s artists were dropping incredible albums by taking unprecedented and unconventional approaches to hip-hop. By contrast, in 2013, many songs seem nearly identical, both sonically and content-wise. Topics like molly and twerking seem unavoidable, and many artists seem to piggyback off of the ideas of others in pathetic attempts to capitalize on what has made other people successful. This lack of originality is a topic that Kendrick himself has addressed. In late May, the Compton MC declared that “molly rap” had become “corny.” The repetitive nature of hip-hop has led to a severe decline in overall quality – how many times do we need to hear a rapper implore us to “turn up, turn up”? Kendrick’s “Control” verse flies in the face of all this – of molly, of “designer s**t,” of the complacency with which rappers collaborate with their peers instead of seeking to outperform them.

From a personal point-of-view, Kendrick is preaching to the choir. As an avid consumer of hip-hop, I am really turned off by the “state of rap.” Even when particular artists disappoint me, I am able to find other MCs to be excited about. While there are certainly some rappers releasing quality music (the Yeezus album was particularly phenomenal), 2013 was the first year since 2006 – the year that Nas famously decreed “Hip Hop Is Dead” – that the genre simply has not appealed to me. My roommate and I both largely turned our backs to contemporary rap this summer, opting instead to listen to old soul and funk records or contemporary soul gems like Quadron or Hiatus Kaiyote. On a typical day, a dozen new rap songs and perhaps one or two new mixtapes will be released. Many of these songs and projects blur together; there is little that sets them apart from what dropped the day before or what will drop the next day. By contrast, many of the songs that we encountered during what we dubbed the “Summer of Soul” stood out for different reasons – the upbeat funkiness of KC & The Sunshine Band’s “(You Said) You’d Gimme Some More” or the infectious smoothness of Bettye Swann’s “Make Me Yours.” Many of these songs often featured sections that, either musically or lyrically, were interpolated by later musicians. Instead of listening to carbon copies, we were finally listening to something truly original from artists who had created something. Where rap was becoming increasingly tiresome, soul music was (and is) a fresher alternative.

It was clear to us that hip-hop needed to be shaken up; that the genre as a whole was, essentially, sleep-walking. On “Control,” Kendrick takes it upon himself to be the force to wake everyone up. His declaration that “this is hip-hop” is simple, and yet just those four words evoke a sense of a lost era of rawness, of competitive edge – an era that Kendrick is doing his best to revive. At the risk of sounding meta, the fact that so many find his “Control” verse to be so important is, in itself, important. Enthusiasm in hip-hop is usually restricted to particular audiences. While a Chance the Rapper mixtape may cause excitement among younger fans, for instance; older audiences are often ambivalent. Kendrick’s “Control” verse, on the other hand, appealed to everyone: older rappers, younger rappers, older fans, younger fans, journalists, bloggers, etc. That so many people were talking about the verse is telling – there is, undoubtedly, a prevailing notion that it was about time someone shook things up. And for the verse to have come from Kendrick, one of, if not the, hottest rapper out there was especially promising. Things seemed, in the immediate aftermath, to be primed for change. Kyambo “Hip Hop” Joshua, co-founder and co-CEO of the famous management and production company “Hip-Hop Since 1978” and close friend of Jay-Z even posted a tweet proclaiming that Kendrick had spit “The most important verse since Kool Moe Dee killed Busy B on Sept 11, 1981 at Harlem World.” While the statement may have been a bit hyperbolic, it certainly reveals just how momentous the Kendrick verse seemed after a first listen.

Alas, the next few weeks quickly reminded hip-hop heads to not raise their hopes too highly. Many MCs painfully attempted to diss Kendrick for his verse, with NY rappers in particular offended by his “King of New York” line. Hearing Papoose diss Kendrick for being shirtless on his album cover (um, he was a baby?) was certainly a disappointing return to reality, a stark reminder that many had (and will continue to) misinterpret Kendrick’s intended meaning. (One notable exception is Joe Budden’s brilliant response). Still, the true consequences of Kendrick’s verse will likely only be revealed after a longer period of time. Hopefully, rappers heed his message and strive to release more quality music in the future. Until then, rap fans can take solace knowing that K-Dot is sitting somewhere with a pen in his hand and a crown on his head readying another verse to blow our minds.

Aazim Jafarey is a junior at Columbia University majoring in Urban Studies. Originally hailing from the Greater Boston area where he graduated from Phillips Academy, Aazim is an avid music listener and hip-hop enthusiast. In his spare time, he is a freelance rapper who records under the pseudonym, Lucid Dreams. You can check out his music at soundcloud.com/iseelucidly and can contact him at [email protected].

Filed under Music · Tagged with 2 chainz, aazim jafarey, age of social networking, big daddy kane, big sean, biggie, breaking bad, drake, j. cole, juicy j, k-dot, kendrick lamar, king kendrick, kurupt, lindsay lohan, michael jackson, modern-day hip-hop, originality has declined, summer of soul, super bowl, the notorious b.i.g, tupac, twitter